What do you see? A ceramic figurine of a dark-complexioned woman who is standing in front of a dented old oil drum doing something? Oh wait! She has a rolling pin in her hand and seems to be rolling out some kind of dough. Well, you’re absolutely correct. But there is a lot more to this figurine than meets the fleeting eye.

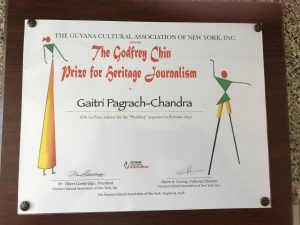

Like all of my Kiskadee Days and Kiskadee Village ceramic sculptures, Meena embodies a chunk of cultural history. Let’s peel back a few layers.

Meena is the descendant of Indian indentured labourers who were taken to work on the sugar plantations of British Guiana. Her ancestors would have been offered the choice of a return passage to India when their contract expired, or a modest land grant. Many chose to remain in the colony and generations later came people like Meena – and me.

They remained largely in rural communities, often near to a sugar estate where they were able to get jobs. Everyday food was basic and based on availability. In a self-sufficient village there would be vegetables from the kitchen gardens, fish from the ponds and trenches, and on more special occasions a home-reared fowl or duck. Very special occasions called for a sheep to be butchered in a Hindu family, while Muslims and Christians might prefer beef. Larger communities near to sugar estates had markets that offered more variety. The indentured labourers and their descendants would, for generations, continue to use Bhojpuri Hindi words in everyday speech, particularly when related to food and cooking.

Getting back to Meena: she is rolling out roti. Paratha, commonly known as ‘oil roti’. The simple dough is rolled out into a thin circle after a short resting period, generously oiled and sprinkled with flour, then a slit is made from the rim to the centre and it is coiled to form a cone. The tip of the cone is pressed inwards to make a navel. These ‘loi’ as they are called in Guyana, are left to rest for while before being rolled out and cooked on a tawa, a flat iron griddle. The job is not quite done, though. The cooked roti is lifted off the tawa at the right moment, when there are just a few golden flecks on its surface, then flung into the air and retrieved with a clapping motion, flakes flying in all directions. After a few flings and claps, the roti loosens up beautifully into the layers that were created by the cone and can be peeled apart into soft and silky fragments. I believe that some people nowadays have taken to putting the roti into a large jug and shaking it vigorously to loosen the layers. It saves your hands but it won’t be the same as a clapped roti. There is a middle road: put the hot roti in a teatowel and then clap it. No flying flakes, no burnt hands. But no fun either.

The old oil drum here, which the villagers call a puncheon, is now so dented and cracked that it’s no longer fit to hold water. It’s still too good to throw away, though. It has been repurposed into a makeshift table and stands in the bottomhouse near the chulha (clay stove also called a fireside). The smooth wooden top makes an excellent rolling surface so there is no need to bring down the chowki (rolling/pastry board) from the proper kitchen upstairs. Meena’s belna (rolling pin) flies back and forth as she expertly produces perfectly round roti every time. No maps of Trinidad here!

From Meena: “Fry bora wid aloo an saalfish done cook. And dis ah de laas loi mih roll out. Now mih cyan ress lil bit before mih husban an dem chirren come home. Mih guh siddung in de hammack an read de Mills an Boon mih baarrow from Liloutie. Mih weary!”

Note that Kiskadee Days is set in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a totally different life back then and cannot be compared to life in modern Guyana. It no longer exists